Sometimes I am haunted by the idea that I want to spend the rest of my life in the basement of the British Museum or an auction house in Hong Kong in the company of the bright ceramics and sublime tea tools of bygone eras. I confess I have written this article to share this passion with you so that we can continue to explore the beauty of tea ceramics together. Consider this visual guide the first step towards realizing my dream. In view of the almost infinite magnitude and inexhaustibility of the subject, we should begin purposefully with an introduction to Chinese ceramic types, and only later should we dive into the details slowly and gradually.

Survival of Ancient Styles

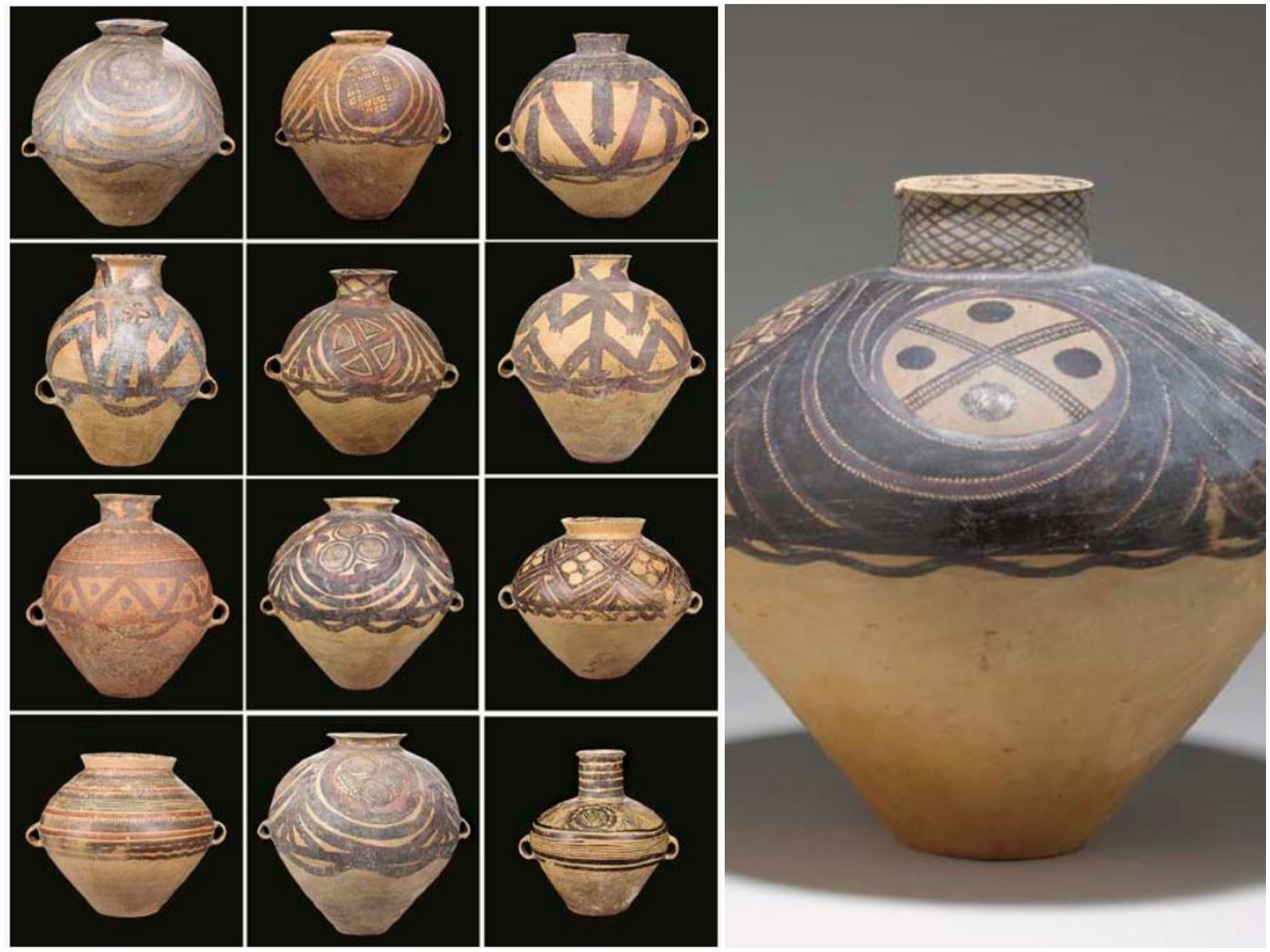

China may never have been completely united, even during the imperial period of its history; it was divided into separate territorial units several times over the millenia. Even so, we can say that the oldest living civilization to have actually survived is in China. Even the first advanced Neolithic cultures, that started to emerge as early as 7000 BC on the territory of present-day China, have a great impact on the appearance of contemporary Chinese ceramics.

The pottery of farming villages, brought on by the independent development of tribal settlements around the Yellow River and the Yangtze River about 7000 years ago, made vessels for a variety of purposes including ceramic jars to store the harvested crops, mortuary and sacrificial objects. Over the millenia of boundless social and technological development following the initial steps, the pottery of the area remained of outstanding standard, and has become a tradition respected and preserved by all artisans.

A group of globular jars with painted curvilinear designs, Neolithic period, Majiyao and Yangshao cultures. Source: Christie’s

Today’s artifacts and tea tools provide valuable information about human past: different historical ages and cultures are reflected in their styles, forms and manufacturing techniques. This is also due to the fact that during the continuous transformation of the empire, internal migration favored cultural transmission as well as the spread of technological achievements. Over the centuries, ceramic art and tea culture had a mutually beneficial relationship; we can say that tea drinking was the direct incentive in the development of some ceramic styles. In other cases, the clay and glazes, that had previously been applied to make storage vessels, sacrificial ewers or mortuary pottery, started to become widely used for producing tea vessels.

Copying, Imitation, Counterfeiting

When studying ceramic styles and unique pieces, it is worth clarifying the difference between these three concepts, as they are a far cry from each other, especially in the eyes of the Chinese. The habit of copying and its role in education still play a huge part in the survival of old styles. Not only does copying provide students with a foundation of practice and a high level of craftsmanship, but even great masters often copy their contemporaries or go back to old forms and styles. In the case of the classical pieces of outstanding artists, the successors look at the creation of the original version as a professional feat and do not think of the masterpiece made in this way as a copy. In this case, the copy is a tribute to its great predecessor.

Zhou Guizhen master potter and her teacher Gu Jingzhou. Source: Taohuren

Copying famous styles and works of art is a tribute to the historical age and the creator, and it reveals that the artisan knows and respects their great predecessors.

Today, imitation is more common. It means that a product is copied in a way that does not exactly match the original piece and then offered for sale under the same name. In the case of counterfeiting, the name of the original maker (not the faker), era or brand is indicated on the item. The seals, signatures, markings, and sometimes the materials used are so faithful to the original that they are suitable to deceive customers and even experts.

This is an issue worth paying attention to as there are rare and prestigious glazes, shapes or works whose low-level copies are worthless, their high-quality copies, however, bear the marks and are carriers of original excellence. In the case of today’s guan or tianmu-style glazes, in the knowledge that they are reminiscent of the Song Dynasty, the glazed wares are referred to as Song Dynasty or Song style ceramics.

Commonly Used Terms: Ceramics, Stoneware, Porcelain, Celadon

Ceramics is a collective term including vessels and other articles made from clay hardened by heat. Stoneware is special pottery in which the clay is obtained by grinding and mixing certain mineral rocks into a powder and then kneading and maturing it with water. Its composition is not the same as that of the clays mined in Hungary. These low-porosity, precision ceramics, fired at very high temperature, unlike their predecessors, are not water-permeable and are much harder, more solid and more durable. Some of their types are burnt white or light gray; these are called porcelain-like clays, which are still used by pottery today in addition to real porcelain. Porcelain is made of a special stone clay, its two distinct components are kaolin and porcelain stone (dunzi), it also contains feldspar, quartz and mica, which make it flexibly formable with high strength and perfect waterproofing properties. In the 16th-17th centuries, porcelain differed significantly from the chunky, usually dark glazed or unglazed earthenware of Europe due to its fineness, strength, and white color, therefore it became extremely popular in a short time. Because of its elasticity, it allowed the use of special decorations and designs, creating an upscale atmosphere at the table. Finally, celadon is a collective term for greenish blue, pale blue and light green monochrome glazed ceramics. The bluish, greenish hues are caused by the varying proportions of iron oxide and titanium oxide mixed in the glaze in a reduction atmosphere. This glaze has been known since the 3rd century and is still very popular today. The Chinese use the term qingzi (greenish blue) for this type of ceramics, the term celadon was coined by European collectors. Celadon pieces have crackle or non-crackle glazes; the crackle pieces exude a wonderful, ancient atmosphere.

The Triple System of Classification

The books presenting Chinese pottery focus on art styles and technological solutions that come with changes in the way of living and thinking within historical ages and dynasties, which are shaping them. In such an approach, it is difficult for us to grasp an object, because if we have a porcelain cup with a lotus flower pattern, we do not necessarily want to follow the stages of porcelain art across dynasties and learn about the negligible differences between the kilns. For us, the main thing is to recognize the style and value of the object and then let ourselves be touched by the technological skills, craft knowledge, artistic sensitivity, intent and message that is present in it.

Returning to the classification of ceramics, we can examine the issues of identification and origin in the following triple system:

- the historical age and dynasty (influences of different ages)

- the art style (colors and glazes)

- famous kilns and ceramic villages.

The dynasty-based classification shows the effects of the spirit of age, social and technological development, prosperity, religious and philosophical tendencies. In this respect, the Song Age can be considered the golden age of Chinese ceramics due to the development of tea culture in the Yuang and Ming Dynasties, when loose tea and gong fu cha first became widespread.

By artistic styles we mean the enrichment of glazes and color variations, which can be related to the gradual discovery of metals and the different colors coming from the burning of metal oxides. Further improvements were made by the enrichment of design and decoration, the appearance of more detailed, more sophisticated vessels.

Famous Kilns were commonly located in areas with easy access to good quality raw materials (nearby clay deposits), fuel (forest areas) and water (transport and processing). From the time of the Five Dynasties and the Tang Dynasty, there were official kilns built and inspected by the imperial court that made the utensils ordered by the court exclusively for them. When kilns were established, they were connected with settlements and were named after them.

Famous Constellations

Here we cannot do without mentioning the two groups according to type, that are often referred to together by ceramic experts, collectors, or lovers of Chinese porcelain. One of them is the group of the famous kilns of the Song Age, including the Five Famous Ceramic Types of the Song Dynasty (五大 名窯 Wu Da Ming Yao): Guan Yao, Ge Yao, Ding Yao, Ru Yao, Jun Yao and Tianmu or Temmoku. The other group is the Four Famous Types of Potteries: Yixing (Jiangsu Province), Nixing Qinzhou (Guangxi Province), Jianshui (Yunnan Province), Anfu Rongchang (Chongqing). I will go into details below.

The great official kilns of the Song Dynasty: Ge, Guan,Ru, Jun, Ding, Jian

Hidden Meaning of Decorations and Shapes

After we identify the art style or the kiln, we examine the form, ornamentation, and motifs used. A teapot or cup will be much more valuable to us if we know the meaning of the motifs, the hidden message of the object. In this respect, we can find ancient motifs (sun, geometric forms), China’s mythological heroes, thoughts of famous philosophers (Confucius, Lao Ce), symbols and figures of the Taoist worldview and Buddhist religion, symbols of fortune, phonemes and stylized images of plants and animals.

Chronology of Events and Cultural Influences

| Date and Dynasty | Ceramic ware and tea culture | Craftsmanship, technology, philosophy, religious thinking |

|---|---|---|

| Neolithic cultures 7000-2000 BC Yangshao culture Longshan culture Majiayao culture |

Clay and ceramic vessels, advanced pottery. Shen Nong discovers tea. Tea spreads as a medicinal herb. Jade carvings, jade jewellery c. 4000 BCE onwards. |

Firing clay in the kiln. Low-fired, porous, vulnerable ceramics. Firing temperature: 600-1100 C. The potter’s wheel is invented, signs of wheel on pottery. Curvilinear designs with circles. Fired red enamel painting, geometrical decoration. Stylized plant and animal patterns, masks. Incisions, polishing. |

| Bronze Age Cultures Xia Dynasty 2100-1700 BC |

Bronze and copper vessels, tools and weapons. Compressed bamboo stick tea, bamboo tea tools, bamboo bowls. Bronze vessels. Yunnan, South-China, the birthplace of tea. |

The discovery of bronze: alloying copper and tin. Metalworking. Taoism: first cosmology, heaven and earth, the role of chi, yin and yang, their influence on human body and mind. The quest for immortality.The invention of writing in China. The Bulang tribe starts to collect tea tree leaves in the forests near the China-Burma border. |

| Bronze Age Cultures Shang Dynasty 1700-1100 BC |

Sacrificial vessels, bronze inscriptions, oracle bones. First South-Chinese (Zhejiang) ash-glazed porcelain. More resistant, solid, non-porous, glazed ceramics. Vases, ritual objects. Porcelain-like ceramics, jade and white marble figurines |

High level of bronze metallurgy. Incised and relief decorations, distinctive animal motifs: tao tie, a monster with large protuberant eyes and horns. Further development of writing. South China (Zhejiang): high-quality clays, kaolinic clays. Wood ash glaze, rich in calcium carbonate imparts a shiny surface to the pottery. Evolution of high firing. Making tea without the addition of other herbs. |

| Zhou Dynasty 1100-221 BC Warring States Period 453/403–221 BC |

Glazed wares, early porcelain. Bronze vessels with detailed ornaments, inlays of gold and silver. Ritual, ceremonial vessels. |

Vertically divided bronze vessels, their vertical division symbolizes the four worlds. Writing on metal vessels. Well-known traditional Chinese motifs: long-tailed sea and celestial dragons, symbols of infinity. Confucius (551- 479 BCE), Lu State. Confucianism Laozi (565- BCE): Tao Te King (The Book of the Way and its Virtue) Sunzi (philosopher, military general, 544 – 496 BCE): The Art of War Laozi describes tea as an elixir of life. |

| Qin Dynasty 221-206 BC | Column 2 Value 5 | Column 3 Value 5 |

| Han Dynasty 206 BC-220 AD | Spread of high-fired stoneware. Glazed ceramic ware. Early ash-glazed celadon. Varnishing, varnished furniture. Silk. Goldsmithing. |

High-fired stoneware, scratch-resistant, less fragile, hard, impermeable, similar to porcelain. Firing temperature:1100-1300 C. Reduction of porosity of clays. Glass manufacture. Inscriptions and calligraphy integrated. |

| Sui Dynasty 589-618 | Column 2 Value 7 | Buddhism and its first patriarch Bodhidharma. Buddhist monks plant tea in the monastic gardens. |

| Tang Dynasty 618-906 | Compressed tea, tea bricks. Lu Yu: Cha Jing Tea tools as found in Lu Yu: The Classic of Tea. Tri-color (San Cai) tomb figures and ceramic ware. |

Early monochrome glazed ceramics (Yan Se You), single-colored, white, blue, red and yellow pieces. Early blue and white porcelain ware (Henan), the use of cobalt oxide coloring (blue). A treatise by Lu Yu tea master on how to grow and prepare tea. Landscape painting reaches maturation. |

| Liao Dynasty 907-1125 | Column 2 Value 9 | Column 3 Value 9 |

| Five Dynasties 951-960 | Column 2 Value 10 | Column 3 Value 10 |

| Song Dynasty 960-1279 | Southern celadon or Longquan celadon, the largest historical ceramic producing area in China. Ceremonial tea sets. Chawan, bamboo whisk, water ewer. |

Longquan celadon. New decorative techniques: Guan and Ge glazes. Grey, blue and green tones depending on proportions of iron oxide in the glaze. Sophisticated tea ceremonies. The tea cultures of the imperial palace, monasteries and common people develop separately. Special tribute teas enjoyed by officials. Tea infusion, whisking. Grey, cream color or white clay body, porcelain-like stoneware. The golden age of monochrome glazed ceramics evoking jade and bronze vessels. Crackle glazes due to thermal expansion and shrinkage. Firing temperature: 1180-1280C. |

| Yuan Dynasty, also called Mongol Dynasty 1269-1368 | Underglaze blue and overglaze red painting. Loose leaf tea production starts. Oolong and black tea from Fujian, Canton. |

The export of tea and tea ware. Floral, animal and human motifs in decoration. The harmony of nature. The three principles of Heaven, Earth and Man represented in ceramic design. |

| Ming Dynasty 1368-1644 Xuande Period 1426-1435 Chenghua Period 1465-1487 Wanli Period 1573-1621 |

Loose leaf tea spreads, green tea varieties develop. The rise of Jingdezhen, a huge ceramic centre. The appearance of reign marks on ceramic ware. Multi-coloured lacquerware. Glass, jade and ivory figurines. |

Early blue and white glazes followed by polychrome ceramics with painted decoration. |

| Qing Dynasty 1644-1911 Kangxi Period 1662-1722 Yongzheng Period 1722-1735 Qianlong Period 1736-1795) Jiaqing Period 1796-1820 Daoguang Period 1821-1850 |

Famous Chinese tea varieties, growing regions and tea processing methods. | Gongfucha spreads throughout China. European influence on Chinese porcelain production and decoration. New colors reflect European taste. On porcelain ware the motifs are taken from nature: flower-bird decoration, animals, landscapes, human figures. |

| Republic of China 1912-1949 |

Column 2 Value 15 | Column 3 Value 15 |

| People’s Republic of China 1949- |

Column 2 Value 16 | Privately owned tea companies with a long history become nationalized. Establishment of the first Yixing teapot factories. Factory products. |

| Modern Age | Tea collections. Ancient tea tools. Following ancient styles. Ancient kilns. International tea conferences. |

The influence of Taiwanese and Japanese traditions (tea ceremony) on tea culture. The opening of the puerh tea market in the late 90s after the return of Hong Kong to China. Taiwan plays an important part in the puerh market. Puerh boom. Rising living standards and quality demands in tea drinking following the boom in Chinese economy. Rediscovery of ancient civilizations and tea cultures. The spread of martial arts and Eastern philosophies in the West. |

Artistic Styles, Colours and Glazes

Yanse you (颜色釉) – Monochrome glazes

Monochrome or single coloured glazes in red, yellow, green, blue, black and white colours. Various colours can be obtained by adding different metal oxide colorants to the white host glaze and firing the objects at different temperatures (1000℃ – 1300℃; low and high) and different atmospheres (oxidation, reduction atmosphere). Three main factors affect the shade of a colored glaze: the formula of the glaze, the firing atmosphere, and the firing temperature. For example, copper oxide is used as a colorant for red glaze, antimony oxide is used for yellow, iron oxide is used for green, manganese oxide is used for purple and black, and cobalt oxide is used for blue glaze. Due to the combined effect of the proportion of metal oxides in the glaze, the traces of other metal elements and the different types of clay, the color of the glazes is different. The first monochrome objects appeared during the Shang dynasty, and their popularity in China has been unbroken ever since. They were praised for evoking noble materials, jade, bronze, ivory, etc. and for reviving the culture of old times with their archaic style.

Famous monochromes: Qing Bai (’blue white’, pale blue), Tian Bai 1 (’sweet white’, cloud white), Tian Bai 2 (’sweet white’, with gentle silky shine) Celadon or Qingzi (’blue green’), Langyao hong (’Lang kiln red’, ox blood red or copper red) Jiang Dou Hong (peachbloom), Yao Bian (’flambé’ glaze, streaked, flaming glaze with blue-purple-brown transitions and spots), Ji Lan (’sacrifice blue’, dark blue), Kongque Lan (’peacock blue’ , turquise blue, deep blue), lacquer black, Chayemo (’tea dust’ glaze, matte greenish brown), pea green, olive green, moss green, Dongqing (Eastern greenish-blue, pale green).

Yan Se You – Monochrome glazes

Post-firing treatments also largely determine the final appearance of ceramic forms. Such can be the rate and suddenness of cooling and the techniques used during cooling. They affect the texture, glossy or matte finish, internal patterns, cracks and stains of the glaze.

Hong You (红釉) – Red glaze

Red-glazed porcelain is considered an art treasure in traditional Chinese ceramics. During the Yuan Dynasty, the first attempt was made in Jingdezhen to burn a glaze mixed with copper oxide, which burned to a bright red color at a sufficiently high temperature (1300 C), in reducing atmosphere. The manufacturing process was very complicated because copper ions are extremely sensitive to temperature; if the kiln is heated a few degrees lower, the glaze turns black, on the other hand, if it is heated hotter, the copper evaporates from the glaze, meaning that the pot will be colorless. The allowable range between the high and low temperatures is about 10 C. In the old days, the temperature control within this range was very difficult, so only experienced potters could achieve the right color. We distinguish between copper red and iron red glazes.

Famous Red Glazes: Ji Xue Hong (’chicken blood red’- copper), Xian Hong (’fresh red’, scarlet red – copper) Langyao Hong (’Lang kiln red’or ox blood red – copper), Jiang Dou Hong (’peachbloom red’, bean red (copper), Bao Shi Hong (’gem red’ or ruby red – copper), Fan Hong (vitriol red – iron), Shan Hu Hong (’coral red’ – iron), Ji Hong (’sacrifice red’– copper)

Typical red glazes: chicken blood, scarlet, ox blood, coral, rose, carmine

The temperature can affect the shade of colour, in this respect iron and copper can yield Xing Zi Shan (orange red peach), slightly yellowish coral, date red and rat breast red glazes.

Fen Cai (粉彩’powdery colours’) – Pastel colored decoration

The technique of fencai coloring was developed in the Yongzheng period of the Qing Dynasty (1722-1735) in Jingdezhen under the influence of paints and colors imported from Europe, catering to the demands of Western taste. During the enamelling and decoration, mainly soft, pastel colors and soothing shades were used, typically on white ground. Common colors were pink, brown, light blue, light green, purple, and other pastel shades.

Pastel color patterns on white ground

Gu Cai – Saturated, antique colors

The gucai style was developed during the Kangxi period of the Qing dynasty. This is a style of decorating white porcelain using saturated colors as opposed to pastel colors. A renewal of the wucai of the Ming, it used a color palette of blue, green, purple, yellow, red and black on meticulously crafted embellishments. Its name, “antique colors” refers to the Ming traditions. We can detect several layers of the embellishment painted in bright, basic colors.

Simple, saturated colors: red, blue, green, purple, yellow, black

Qing Hua (青花) – Blue and white painted porcelain

Blue underglaze paintings on white ground. After the first firing, white pottery or porcelain was decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment mixed with cobalt oxide. When it dried, the pot was dipped in a colorless glaze, which was fixed with a second firing. In the case of masterpieces, the richness of shades and forms, along with the masterful brushwork, determined the rank of the vessel, if it was designed for imperial, court, or common use. The decoration technique known since the Tang dynasty lived its heyday in the Ming age, and were further developed in the Jingdezhen kilns which were rebuilt during the Qing dynasty. This porcelain style made up the bulk of European exports. The subject matter for the decorative images were often dragon and phoenix, flowers, birds, landscapes, human figures, legendary or mythological heroes, Buddhist and Taoist symbols.

Underglazed blue decoration

Dou Cai (斗彩) – Underglaze blue, overglaze different colours

In this style, the outlines of the decoration were drawn by underglaze blue painting, and then, after firing, the pattern was filled with red, green, yellow, black or purple overglaze enamels. It was first used in the 15th century to paint birds, flowers and plants.

Underglaze blue, overglaze enamel painting

Qian Jiang Cai (浅洚山水)

Elegant landscape and calligraphy compositions from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. The compositions incorporate landscape painting, poetry and calligraphic inscriptions. The decoration of the porcelain is meticulous and rich, and represents various subjects such as landscapes, human figures, flowers, birds, fish and insects.

Incorporating painting and calligraphic inscriptions

Fa Lang Cai (珐琅彩)

The imperial style of the Qing dynasty, with its solemn, meticulously crafted fine porcelain in rich colors, was exclusively made for the imperial court by master craftsmen. The makers were not ordinary potters, but the best professional painters in the imperial workshop, so these works of art represent the highest level of art and craft at the time. Enamel paints were imported from Europe, and the color and design represent the splendor of the Western nobility. European style medallions with fine miniature painting and harsh enamels filled in within outlines were very common.

Harsh colours, medallion decoration, fine detailed painting

San Cai (三彩)

Alacsony hőfokon kiégetett három-színű mázas kerámia, jellemzően zöld, barna és sárga foltok és motívumok krémszínű alapon való alkalmazásai. Először a Tang-kori sírkerámiákon alkalmazták ezt a stílust, számos állatszobor, szentek figurái, mitikus lények, rituális edények és közemberek kicsinyített másai készültek ebben ilyen módon. Eredete: Shaanxi, Henan, 7. század.

Low-temperature glazed pottery coated with tri-colour glaze of green, amber and brown splashes and motifs on cream base. This style was first applied to Tang dynasty burial objects; many animal statues, figures of saints, mythical creatures, ritual vessels, and scale copies of common people were made in this way. It originated in Shaanxi, Henan in the 7th century.

Decoration on cream base with green, yellow and brown splashes and motifs

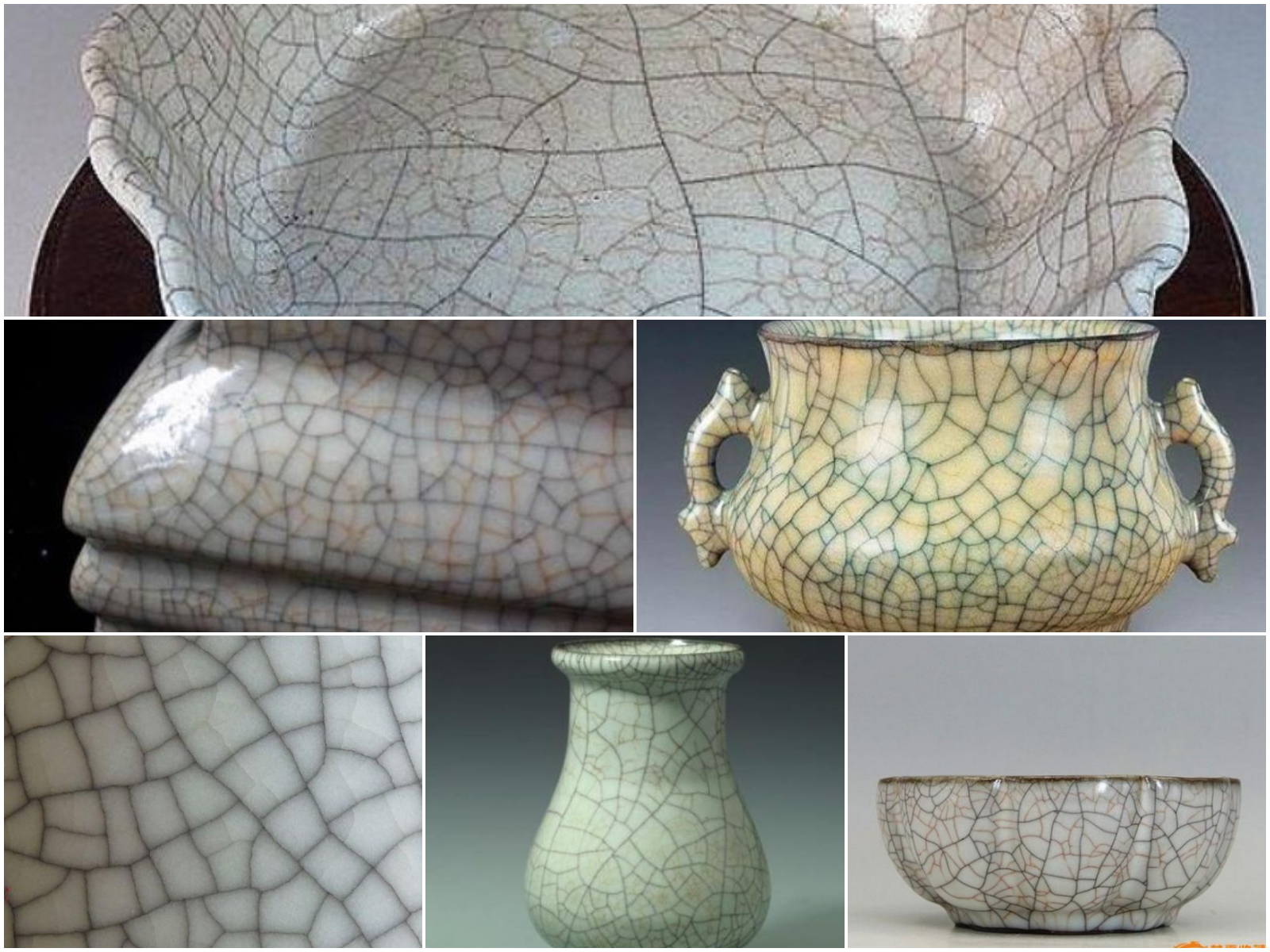

Kai Pian (开) – Crackle glaze

’Opening cracks’, crackle glaze. The crackling in some glazes is naturally caused by the firing and cooling process because of the differences in the degree of expansion of the clay and the glaze. On cooling the glaze shrinks more than the clay body. This was originally an imperfection in technology, but starting from the observed regularities, it later became a consciously added aesthetic element. Such vessels were made in the Ru, Guan and Ge kilns of the Song Dynasty.

Types of crackle glaze:

Ice crackle (冰 裂纹, bing lie wen) glaze: Tight, gap-free, so the tea does not seep into the cracks. In this case, there are no discolorations in the vessel during use, it retains its crystal clear character.

„Civilian and military affairs” style (文武, wenwu): The whole body of the ceramic glaze is split both vertically and horizontally with longer, irregular cracks and shorter crackles on the surface. The longer, amorphous cracks symbolize civilian affairs, the shorter, connecting, straight lines between them symbolize martial arts or military maneuvers. It is a distinctive characteristic of Ge and Guan ware.

Fish scale style (鱼鳞, yulin): In very thick glaze, scaly, multilayered, dense cracks of similar size and pattern appear. It is typical of Ru, Guan and Longquan ware.

„Golden thread and iron wire” style (金丝铁线, jinsi tiexian): There are large and small crackles, in the glaze, the large crackles are dark gray like iron, the small crackles are light brown like golden silk thread. Ge yao pots display this pattern of colored crackles.

Cha Ye Mo – Tea dust glaze

Owing to its components, iron, magnesium and silicic acid, high-fired tea dust glaze is formulated to produce a brownish, yellowish crystalline layer or speckled pattern on a greenish ground. It was first produced in the kilns at Shaanxi, Henan during the Tang dynasty.

Bao Jin / Miao Jin / Liu Jin – Gold intarsia and gilding

Gilding is an ancient handicraft from the Han era. Gilding or gold-plating has always endowed the object and its wearer with value and dignity. Gilding can be the use of a full-surface mercury-gold coating, the application of gold leaf, the insertion of gold intarsia or gold varnish decoration.

You Li Hong – Underglaze red

Underglaze red decoration was developed in Jingdezhen during the Yuan dinasty. There are two types of atmosphere while the kiln is firing: oxidation and reduction. Sufficient oxygen enters with the kiln door open, reduction (oxygen deficient) firing is done with the door closed. Underglaze red is fired under reduction; copper, used as coloring agent, gives red in reduction atmosphere. As it was difficult to control the temperature of the wood-fired kiln, the technical complexity of the process increased the rank and value of red decoration. The painted decoration has to be nice deep red color instead of being black or pale, moreover, the different shades also require extra care and a high level of knowledge.

Underglaze red decoration

Qing Hua You Li Hong – Underglaze blue and red

This decoration requires the combined use of copper oxide and cobalt oxide, which is very difficult to achieve due to the different behavior of the two metal oxides. The ceramic is decorated under the glaze, then it is covered with translucent glaze and finally fired. As copper and cobalt require a different atmosphere, firing is complicated and takes place in several steps, with covers. The two colors together is an expression of stability and a high degree of technical skills in the porcelain object.

The combination of underglaze blue and red, the most difficult technique.

The combination of underglaze blue and red

Wu Cai (五彩) – Five-color decoration

It was developed in Jingdezhen during the Kangxi period (1661-1722) of the Qing dynasty. Strong, vivid colours were applied as decoration. Underglaze blue was very common for the main motifs, which was enriched with overglaze brushwork of different colours. Wucai, meaning „five colors”, refers to yellow, blue, white, red and black which signify the five elements, earth, wood, metal, fire and water and are often identified with north (black), south (red), east (blue), west (white) and the centre (yellow).

Underglaze blue for the design outline, overglaze decoration of different colours.

Five-color decoration

Su San Cai (素三彩)

Susancai is a more refined version of sancai, redefined by Jingdezhen’s porcelain craftsmen with more meticulous patterns, more elegant forms and a wider range of shades. The prevalent colours are the same: green, yellow and brown with occassional black. It thrived in the Kangxi period (1654-1722) of the Qing dynasty.

Fa Hua Cai (法华彩)

The origins of this style date back to the Yuan dynasty. One of its characteristics is that the nitrate-containing additives make the shades of blue and purple brighter and more saturated. Another characteristic is that before painting, the outlines are drawn on the vessel with clay paste, and then the resulting pattern is filled with colors. Low-temperature glaze, first used in Shaanxi and Jiangxi Provinces in the 14th century.

Famous Kilns and Ceramic Centres – Yao (窑)

In China, the imperial courts used ceramics with different material compositions and different color of glaze (jade green, sky blue, yellow, red), which were not allowed to be used by common people. The relocation of the civilization centre or capital gave rise to new kiln villages and towns, which made ceramic ware from local ingredients in a style appropriate to the technology of the age and desired by the court. From the 12th century, not only the imperial court but also provincial officials and the common people used different kinds of porcelain; only porcelain made for the general public could be exported abroad. The glazes, colors and styles associated with famous ceramics centers became well known in later times, which led to a resumption of pottery production in old villages and a resurgence of traditional and antique styles. These styles are identified by the names of the ceramic centers.

Jun Yao (鈞窑 , Jun ware) – Song Dynasty Celadon

One of the „Five Famous Wares” of the Song dynasty. It was first made in the kilns located in Jun County, Henan Province, and later spread to Hebei, Shanxi, Shangdong and Zhejiang provinces. Its distinctive feature is the thick lavender-blue glaze applied to a generally thick vessel body, which often shows splashes of purple or red of copper origin.

Jun glaze with blue and purple stains

Ru Yao (汝窑, Ru ware) – Song Dynasty Celadon

It is also one of the famous wares of the Song Age, made exclusively in imperial kilns in Ru County, Henan Province. It owes its peculiarity to a glaze of surprisingly even thickness applied to the gray or light brown clay body, thus beautifully showing the original shape of the object, resulting in a more refined vessel. The color of the glaze is pale bluish gray or lichen green, depending on the added metal oxides. It has a soft, silky texture and the waxy surface is covered with fine crackle network. The cracks in the structure change slightly to brown when in use, eventually covering the entire cup with a membrain similar to fine cicada wings.

Fine crackles (cicada wings) in the waxy glaze

Guan Yao (官窑, Guan ware) – Song Dynasty Celadon

One of the „Five Famous Wares” of the Song dynasty. Guan yao means „official ware”, ordered by the imperial court and manufactured in one of the imperial workshops. The glaze colors included pale grey, greyish blue, lavender blue, greenish grey or greyish brown. The crackles were wider than in other ceramic glazes, which gave an archaic, noble effect enhanced by the coloring of the crackles. The coloured crackles show the evolution of the manufacturing techniques and superior crafsmanship.

Thick, glass-like glaze with conspicuous crackles

Ge Yao (哥窑, Ge ware) – Song Dynasty Celadon

During the Southern Song dynasty, there lived two brothers in Longquan County and both were potters. The sources say that the ceramic ware made in the kiln of the elder brother were finely crackled with large and small crackles in them, commonly referred to as „golden thread and iron wire”. The color of the glaze is varying in the shades of celadon, but the cream is particularly beautiful. Larger cracks are painted dark gray and the smaller ones light brown. The vessels have shiny, smooth surface.

Waxy glaze with large and small crackles

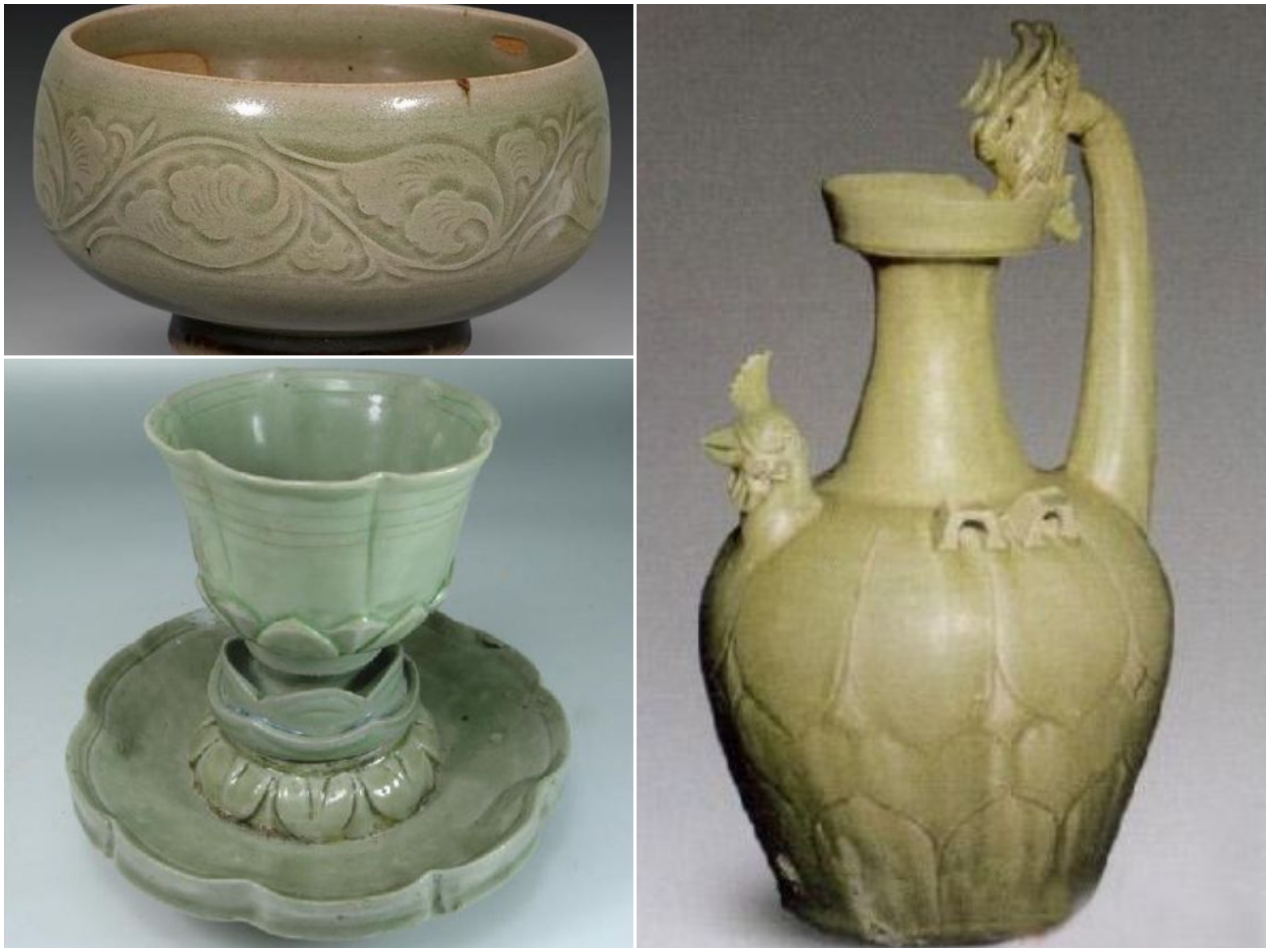

Longquan Yao (龍泉青窑, Longquan ware) – Song Dynasty Celadon

A representative kiln of the Southern Song dynasty that produced thick, shiny, glass-glazed, crackled ware. The typically green or bluish-green glaze is applied to the almost white or light gray stoneware made from local mineral recources. Longquan celadon was manufactured in large quantities and exported to other countries in Asia, which had an important role in the commencement of Japanese and Korean celadon. The style was named after the town of Longquan, Zhejiang Province, where the first kilns were established. Clay and glaze with a high content of iron and titanium, when burned at high temperatures in a highly reducing atmosphere give more greenish, whereas in less reducing atmosphere give more greyish colors. Green-glazed ware with incised decoration or clay-paste relief is very common.

Greenish-glazed, glossy celadon with moulded decoration or undecorated

Ding Yao (定窑, Ding ware) – Song Dynasty Celadon

One of the „Five Famous Wares” of the Song period, which had its roots in the Tang dynasty and reached a peak during the Song dynasty. It was named after its place of origin, the Ding Prefecture, Hebei Province. The style is characterized by decorating the surface of thin, white clay ceramic ware with incised or engraved patterns and then coating it with a translucent glaze, fired at very high temperature (1300-1340 C°) in oxidation atmosphere, which produces an ivory-like glaze. The pieces were given a metal rim in copper, bronze, etc. The hidden, carved decorations on the clay body, the design in shallow relief, floral and plant motifs coated with white glaze create sculpture-like effect, and make it even more opulent. This anhua decoration is one of the distinctive characteristics of Ding ware.

White-glazed clay body decorated with moulded floral patterns and motifs

Yue Yao (越窑, Yue ware)

Originating in the kilns of Northern Zheijang in the Yue Kingdom (Eastern Han period), this early glass-glazed stoneware has stone clay body with very thin olive green ash glaze. Over the centuries, its form evolved becoming thinner and more elaborated. This style, which is considered the ancestor of the Song celadons, and is the earliest type of celadon from the 3rd century, had become very popular by the Tang dynasty. It is characterised by animal and plant ornaments, sculpted decorations (chicken-head ewer), incised and moulded patterning and a paper-thin greenish glaze. It is easy to mix with Yaozhou Yao pottery, nevertheless, kept simple and creates a much more archaic impression.

Early celadon ware produced in the 3rd century

Jizhou Yao (吉州窑, Jizhou ware)

The Jizhou kilns were built during the Tang dynasty in the old Jizhou County (now Ji’an County), Jiangxi Province to produce richly decorated ceramics. Jizhou ware is characterized by figural decoration and elaborate motifs on a black glazed body, which differ from Jian Yao ‘s black glazed ceramics inasmuch as it does not show abstract stains caused by metal compounds, but recognizable organic (leaves, floral patterns) and non-organic shapes. The most typical ones are the black and sauce-brown glazed ceramics with a variety of decoration techniques: tortoise glaze, leaf pattern and figural decorations with traditional paper cut-outs.

Bluish-white glaze with moulded and incised decoration

Hutian Yao

In this village, very high quality ceramics were made, paper-thin with a bluish lustrous glaze. The basic form is embossed or sculptural, with a patterned body on which a translucent, blue-glossy (lake-coloured) glaze is fired. The sculptural clay body, made of grey or white porcelain, is a highly crafted work of art, with bluish shades of glaze and a lustrous jade carving effect. The carving, drawing and sculpting in this style is particularly impressive, with leaves, flowers, waves and clouds full of life.

Yaozhou Yao (耀州窑, Yaozhou ware)

The Yaozhou celadon kiln was located in the Yaozhou district of Tongchuan, Shaanxi Province. The beautifully incised or moulded clay is coated with thin olive green glaze. The decorative lines are sharp, the motif is accentuated by pooling of the glaze in the moulded depressions enhancing the jade carving effect with the different shades of green.

Dehua Yao (德化陶窑, Dehua porcelain)

The Dehua kiln in Fujian Province began to produce its white porcelain in the Song period, but it reached a peak during the Qing dynasty. Glossy, white-glazed figures, moulded patterns, relief decorations are its most common characteristics. It evokes the noble appearence of ivory carvings.

The kiln was established in Jianyang, Fujian Province during the Tang dynasty and flourished in the Song period. The wares are distinguished by their glossy black, glass-like surface with characteristic stains and metallic discolorations in the glaze caused by various metal oxides. Under the Song dynasty, Jian ware was exclusively produced for the imperial court. They were typically used for drinking tea because black bowls better showed the cream color of the pan-fried, powdered, whisked tea. Jian style is distinguished by the coarse, thickly potted, black or greyish-black clay body, glazed with local mineral-rich clay, which produces distinct patterns as it melts. The main types of glaze patterns are ‘hare’s fur’, ‘oil spot’, ‘partridge feathers’, ‘yaobian’ and ‘tea dust’.

Abstract patterns of metallic discoloration in the black glaze

Shufu Yao (樞府, ’Privy Council’)

White-glazed porcelain ware first produced in the Jingdezhen kiln during the Yuan dynasty by firing bluish-white porcelain clay. These egg-white ceramics with a soft blue glow are decorated with twisted branches, flowers, clouds and dragon reliefs; sophisticated vessels made for the imperial officers of the Yuan dynasty.

White glazed ceramics with abundant relief ornamentation

Jian Yao (tyien jáo) – Temmoku/Tianmu

A kiln established in the city of Jianyang, Fujian province, during the late Tang period, which flourished during the Song Dynasty. It is generally characterised by a black glossy surface, with distinctive stains and metallic discolourations in the glaze, caused by the various metallic oxides in the glaze mixture. In the Song period, Jian kiln-fired pots were used only by the imperial court. Teacups were the most typical design, as the black harmonised well with the cream-coloured foam of Song-period roasted, powdered tea. It is characterised by a thick, coarse-grained local ore glaze fired onto black or greyish-black clay, which produces unusual patterns. The most common patterns are rabbit hair, oil drop, rabbit feather, yaobian and tea powder glaze.

Temmoku or Tianmu glaze

Cizhou Yao (磁州窑, Cizhou ware)

Cizhou ware originated in the kilns of Ci County, Hebei Province. Cizhou-type ceramics were produced from the Song dynasty throughout the Ming,Yuan and Qing periods. The most common form of decoration is the black pattern and figures on a white base. The craftsmen of the kiln combined traditional painting and calligraphic art techniques to create a style of black painting on a white background. Though Cizhou ware has been known as popular, the pieces are desired to collectors and art connoisseurs.

Black painting on white ground

Xing Yao (邢窑, Xing ware)

The Xing kiln was located at the foot of the Taihang mountains in Xingtai, Hebei Province. It began production during the Five dynasties, yet it was revived and flourished during the Tang dynasty. Yue celadons dominated the court and the market, the production of pure white porcelain was to counterbalance their prevalence. The two kilns became known under the name of ‘northern white’ and ‘southern green’. Xing porcelain laid the foundation for white porcelain and painted white porcelain in China, and anticipated the fame of Jingdezhen. It is one of the earliest porcelain ware. The white porcelain of the Xing kiln is characterized by its elegant shapes, smooth lines and glossy white glaze. According to the Classic of Tea, Lu Yu „Xing porcelain is silver, Yue porcelain is jade” or „Xing porcelain is snow, Yue porcelain is ice”.

Elegant, sleek and simple porcelain ware

Yixing pottery

Local purple clay (zisha) has been used to make pottery for thousands of years in Yixing. The mountains around the village of Dingshu on the shores of Lake Taihu, rich in clay of various colors and properties due to the high content of clay minerals, gave rise to the establishment of numerous kilns. In Yixing, which initially specialized in the production of cooking and storage vessels, the manufacturing of teapots began in the 16th century (Wanli period, Ming dynasty) with the appearance of loose-leaf tea. Instead of craft industry, finer crafsmanship by the hands of master artisans came to the fore. Created using local clays, the high-strength, finely textured pieces of various forms carry an unprecedented unity of aesthetics and function to make our teas much finer. The walls of the hand-built, beautifully sculpted, unglazed clay pots are both breathable and have excellent heat-retaining properties.

Yixing pots embellished with calligraphy and incised decoration

Qinzhou Nixing pottery

Nixing pottery in Guangxi Province has a history of more than 1000 years. Although not as significant as Yixing, in recent years this type of clay ware has again become popular with collectors and tea drinkers. The ancient city of qinzhou is famous for its peculiar red clay from which artisans make wonderful, bronze-colored, high-strength tea tools with a metallic effect. The teapots are fired under high temperature, and then polished to add extra shine. A special feature of Nixing ceramics is that they keep the tea leaves fresh and the tea brew retains its aroma in them for a long time.

Nixing teapots in reddish brown color with a bluish tinge

Jianshui pottery

The Jianshui teapot is a nearly 200-year-old work of many generations in a small town in the Yunnan Autonomous Region. Similar to Yixing, it is made in a variety of colors, depending on the mineral composition of the clay excavated from the local clay deposits. The pots are shaped on a wheel and polished to a high gloss, as if they were glazed; the solid, yet breathable walls keep the heat even and bring out the flavor of the tea. Due to their fresh-keeping properties, plenty of teapots, cooking pots and vases are made here, as the flowers live longer in the vases, and the food stays fresh longer in the pots. It is distinguished by the use of colorful clay inlays which is made by engraving the decoration into the clay body and filling the engravings with clay of different colors. The excess clay is then removed, the teapot is polished and fired, resulting in an exquisite teapot decorated with antique patterns, engravings, inlays and calligraphy. When you knock on it, it makes a metallic sound.

Polished clay teapots decorated with inlays

Rongchang Anfu pottery

Rongchang pottery has been produced in Anfu Town, Rongchang District, Chongqing Municipality, Sichuan since the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD). From ancient times to the present day, pots have been continuously made here for the common people, and now Anfu pottery is listed as state-level cultural heritage. Anfu pottery enjoys great fame for its fine clay, which is “as thin as paper, as resonant as chime stone (a percussion instrument made of stone), and as bright as mirror”. The color of raw clay, the refined forms, decorated with folk motifs, give this pottery a sleek, elegant feel.

We haven’t finished yet:), this article is too long, I reserve the right to make changes. If you have time, you should also watch this video, parts 1-4!

Enjoy your tea and the beautiful tea tools that surround it.

Leave A Comment